Filmmakers for the Prosecution

WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY JEAN-CHRISTOPHE KLOTZ, adapted from Sandra Schulberg’s article “Filmmakers for the Prosecution.”

Produced by Céline Nusse, Paul Rozenberg, and Sandra Schulberg with the support of ARTE and La Fondation pour la Mémorial de la Shoah.

2022 / 60+ Minutes / In English and French with English Subtitles

Distributed by Kino Lorber

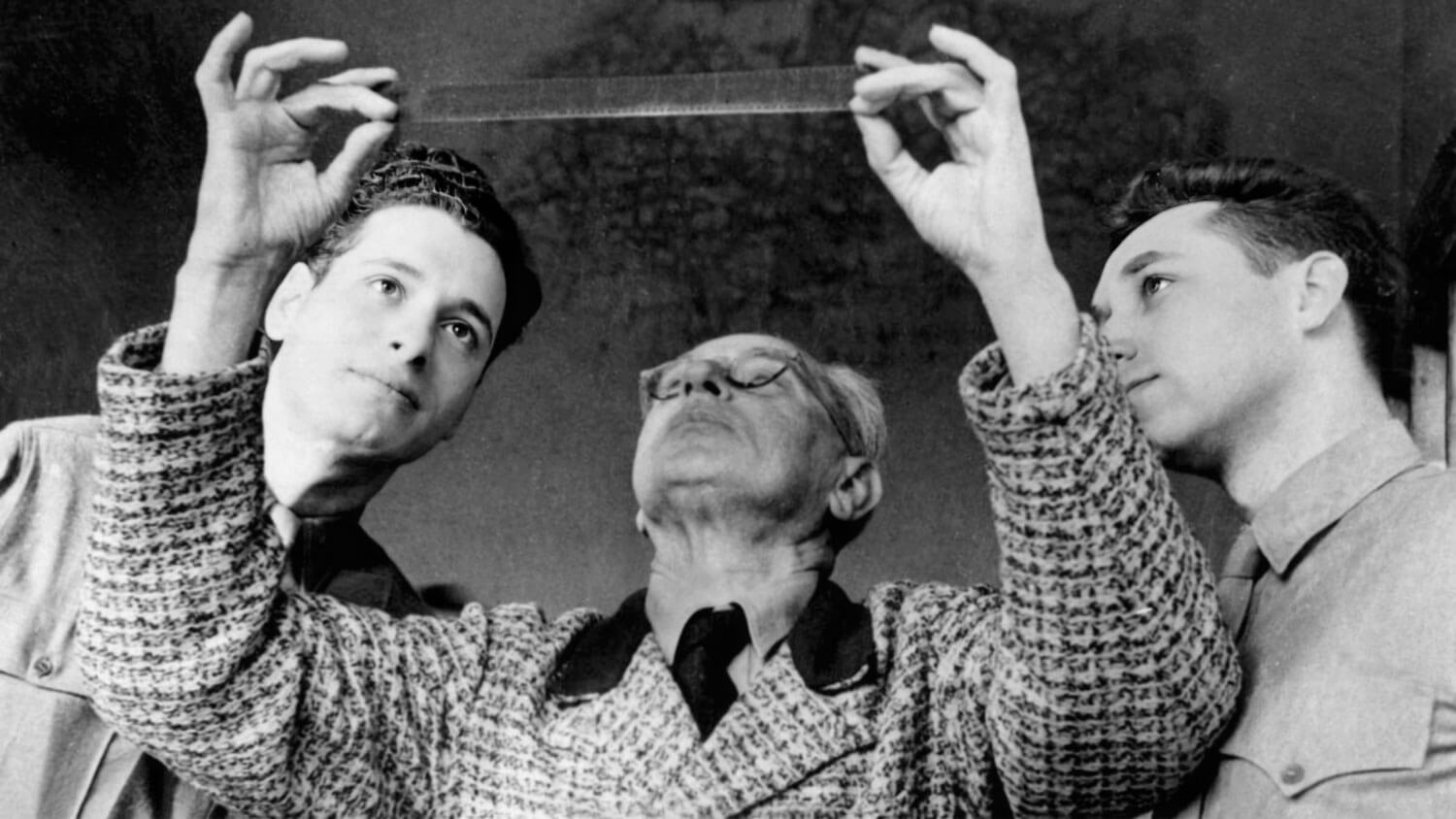

OSS officer Stuart Schulberg (at right) examines film evidence with Hitler’s photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, who was forced to cede his 12,000 photographs to the OSS team. (Schulberg Family Archive)

This is the amazing true story of the OSS officers who tracked down the films used to convict the Nazis, a startling example of the power of the moving image to change hearts and minds and to indelibly shape our collective memory. It features newly-discovered archival footage about their search and their presentation of the films as evidence in a court of law — a historical first — at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, the first of 13 Nuremberg trials.

The story is carried by Eli Rosenbaum, who served for 30 years in the Office of Special Investigations of the U.S. Department of Justice, prosecuting Nazis in the U.S. and extraditing others to await trial in Germany. In June, U.S. Attorney General Merrick B. Garland named Mr. Rosenbaum Counselor for War Crimes Accountability with the mandate “to pursue law enforcement accountability for grave crimes committed in the wake of Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine.” As Rosenbaum explains in the film, the “Nuremberg principles” underlie all modern attempts to prosecute crimes against humanity and crimes against the peace.

Filmmakers for the Prosecution features jaw-dropping first-hand accounts by Budd Schulberg, head of the OSS search team; Niklas Frank, son of Nuremberg defendant Hans Frank; and French jurist Yves Beigbeder, assistant to French judge Henri Donnedieu de Vabres; fascinating reveals by scholars Sylvie Lindeperg, Axel Fischer, Alexander Zöller, and Stuart Leibman; and illuminating comments from Sandra Schulberg about the decision to suppress the American film about the Nuremberg trial as the Cold War began.

Our collective memory of the Nazi period is founded on the evidence collected by the Schulbergs and shown during the first Nuremberg trial. The images they presented in the courtroom are famous, but the story of the Schulbergs’ search has not been told on film until now. The inside story of their extraordinary mission comes to life through never-before-seen footage of the Schulbergs and through their private letters. The importance of their work is put in context by Eli Rosenbaum, an expert on the Nuremberg principles, who is now the U.S. Department of Justice Counselor for War Crimes Accountability in Ukraine.

Seventy-five years after the trial, French journalist and filmmaker Jean-Christophe Klotz returns to the German salt mines where Budd Schulberg discovered film footage still burning and recreates the finding of secret caches described by both the brothers. By interviewing key surviving figures in the story he then unravels the mystery behind why the resulting film about the trial — Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today — was intentionally buried by the U.S. Department of War. Klotz’s riveting film also fills in the gaps of how these groundbreaking materials were sourced, and poses still-pertinent and profound questions about the process of using film to write history.

Filmmakers for the Prosecution is adapted from Sandra Schulberg’s eponymous monograph which documents her years of research into the OSS film unit’s work for the Nuremberg trial. Daughter of Stuart and niece of Budd, she produced the film with French partners Celine Nusse and Paul Rozenberg. The film’s European version premiered at the 2022 New York Jewish Film Festival as The Lost Film of Nuremberg. Since then a new American version has been produced by Sandra Schulberg and Josh Waletzky with new narration by Jessica DiSalvo. Budd Schulberg’s son Benn Schulberg reads excepts from his father’s account; and Stuart Schulberg’s son KC Schulberg reads excerpts from his father’s letters. The American version has more end credits and a longer runtime of 65 minutes.

The Schulberg brothers — Stuart at left, Budd at right — worked in the same OSS film unit throughout the war and during preparation for the Nuremberg trial. (Schulberg Family Archive)

Synopsis

It’s the summer of 1945 at the end of World War II. Movie legend John Ford, head of the Field Photographic Branch of OSS (America’s wartime spy agency), assigns brothers Budd and Stuart Schulberg to carry out a special mission. Their task — to track down German footage and photographs of Nazi atrocities in order to convict the Nazi leaders scheduled to stand trial in Nuremberg that autumn.

So begins a high-stakes four-month investigation that takes the two young men across a devasted Europe in search of visual evidence of the most heinous crimes in history. Older brother Budd has already caused a sensation with his first novel, the Hollywood exposé What Makes Sammy Run?, but this is years before he wins the Oscar for writing On The Waterfront. Stuart, a University of Chicago drop-out, has high hopes of a career in journalism but is a lowly newspaper copy boy when he quits to join the Marine Corps after Pearl Harbor. This is years before he will become the Emmy-winning producer of David Brinkley’s Journal and then producer of NBC’s morning news juggernaut, Today.

DIRECTOR

Jean-Christophe Klotz

A journalist and war correspondent by training, Jean-Christophe Klotz’s reporting took him to Rwanda to document the genocide and its aftermath in three films, Kigali, des images contre un massacre (2006), Lignes de front (2009) and Retour a Kigali (2019). Mogadishu in Agony is his portrait of the Somali capital ravaged by civil war and famine. He also makes films about American society and culture, notably The Routes of Terror about 9/11; The Race for Black Gold, about the Sino-US oil rivalry; and John Ford, The Man Who Invented America. His latest films, commissioned by ARTE, include portrait of Bret Easton Ellis, and a forthcoming film about the making of Soylent Green.

CO-PRODUCER

After restoring Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today, Sandra Schulberg served on the front lines of Ben Ferencz’s campaign for international criminal justice and helped develop a film about him, Prosecuting Evil, by Barry Avrich. The last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor, Ben Ferencz turned 102 in March 2022. Schulberg is now president of IndieCollect, a non-profit organization whose mission is to rescue, restore, and reactivate extraordinary American independent films. IndieCollect has archived thousands of abandoned film negatives since 2013. Her latest restorations include F.T.A. produced by and starring Jane Fonda, Nationtime, Cane River, Jazz on a Summer’s Day, Thank You and Good Night, Thousand Pieces of Gold, and The War At Home. Before turning to restoration, Schulberg was a producer and advocate for “Off-Hollywood” filmmakers, founding the IFP in 1978-79 and co-founding First Run Features in 1980. Her movie credits include Waiting for the Moon, winner of the Sundance Grand Prize.

NUREMBERG: Its Lesson for Today

The greatest courtroom drama in history

Written & Directed by Stuart Schulberg

Restored by Sandra Schulberg & Josh Waletzky

80 minutes, B&W, 35mm, Mono, Aspect Ratio 1:33;

English & German (some French & Russian) with English Subtitles

The 2009 film-to-film restoration and subsequent digital edition were funded by Leon Constantiner, Whitney Green, Whitney & Anna Harris, Maurice Kanbar, Michael Ratner, Steven Spielberg, Evelyn Stern, Nancy Meyer & Marc Weiss, Peter & Cora Weiss, Helen Zukerman, Fledgling Fund, Elizabeth Meyer Lorentz Fund, Irving Harris Foundation, Planethood Foundation, Righteous Persons Foundation, Samuel Rubin Foundation, and with support from the Nationaal Archief of The Netherlands, Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, and Open Society Foundations.

Special Thanks to John Q. Barrett, Cherif Bassiouni, Michael Berenbaum, Ed Carter, Sandra Coliver, Karen Cooper, Christian Delage, Israel Ehrisman, Raye Farr, Donald & Benjamin Ferencz, Gregory S. Gordon, Karl Griep, Elwin Hendrikse, Annette Insdorf, Dieter Kosslick, Amichai Lau-Lavie, Rachel Levin, Bruce Levy, Jeff Lipsky, Ernst Michel, Aryeh Neier, Paco de Onis, Gregory Peterson, Mike Pogorzelski, Stephen J. Rapp, Sybil Robson, John Roche, Tony Rodriguez, Eli Rosenbaum, Jerome Rudes, Leila Sadat, William Schabas, Michael P. Scharf, David J. Scheffer, Liev Schreiber, Leslie Swift, Margery Tabankin, Dan & Toby Talbot, Magda Pollaczek Tisza, Heikelina Verrijn-Stuart, Leslie Waffen, Robert Wolfe, Irwin Young, Lindsay Zarwell, the Robert H. Jackson Center, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the families of Liselotte Balte Ashkins, Emilio DiPalma, Daniel Fuchs, Dan Kiley, Pare Lorentz, Robert Parrish, Budd, Sonya & Stuart Schulberg, Robert Webb, Joseph Zigman.

Robert H. Jackson, chief US prosecutor at the Nuremberg International Miltary Tribunal. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today depicts the most famous courtroom drama in modern times, and the first to make extensive use of film as evidence. It was also the first trial to be extensively documented, aurally and visually. All of the proceedings, which lasted for nearly 11 months, were recorded. And though the trial was filmed while it was happening, strict limits were placed on the Army Signal Corps cameramen by the Office of Criminal Counsel. In the end, they were permitted to film only about 25 hours over the entire course of the trial. This was to prove a great impediment for writer/director Stuart Schulberg, and his editor Joseph Zigman, when they were engaged to make the official film about the trial, in 1946, shortly after its conclusion.

“HAUNTING AND VIVID.

What this documentary shows is how a vital and

indispensable principle of humanity was restored.”

— A. O. Scott

“CRITICS’ PICK! RIVETING.

More powerful than any fictional courtroom drama could hope to be.”

— Bilge Ebiri

“ MESMERIZING.

‘Nuremberg’ couldn’t be more of the moment.

Something of a minor miracle.”

— Ann Hornaday

“ POWERFUL. A DEFINITIVE REBUKE TO ALL HOLOCAUST DENIERS.”

— Lou Lumenick

The Film's Structure and Content

Poster from the release of The Schulberg/Waletzky Restoration

Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today follows the structure of the trial, using the four counts of the indictment as its organizing principle. While much of the film is set in the courtroom, Nuremberg reconstructs the prosecution’s case and rebuts the defendants’ assertions by relying on the Nazis’ own films. Nuremberg therefore cuts back and forth to these films.

Justice Jackson’s Opening Statement

The film opens with a woman emerging from a hole in the ground, carrying a naked infant. The surrounding landscape consists of mountains of rubble. A civilization has been destroyed but slowly, slowly, people nurture life again. A woman puts a plant on a windowsill; a man, with a little boy at his side, plays a violin. “How did it happen?” the narrator asks, “What were the forces?” And then the film cuts to the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, one of the few buildings still standing in the ruined city. U.S. Chief Prosecutor, Robert H. Jackson, a Justice of the United States Supreme Court, makes the opening statement:

“The privilege of opening the first trial in history for crimes against the peace of the world imposes a grave responsibility. The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant and so devastating, that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored because it cannot survive their being repeated. That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.”

Justice Jackson’s Closing Statement

Nuremberg builds to its conclusion with the final summations of the four chief prosecutors, and the verdict of the panel of judges. Many people do not realize that three of the defendants were acquitted. Then it cuts to the prison, which was part of the Palace of Justice, and to exterior shots of the cells of those prisoners condemned to hang. The last shot of the film echoes a mysterious figure that we’ve glimpsed in front the courthouse, but that we could not make out. Now we see it is a statue of Jesus on the cross, emerging from the rubble. The final frames of the film carry Jackson’s parting words:

“This trial is part of the great effort to make the peace more secure. It constitutes juridical action of a kind to ensure that those who start a war will pay for it personally. Nuremberg stands as a warning to all those who plan and wage aggressive war.”

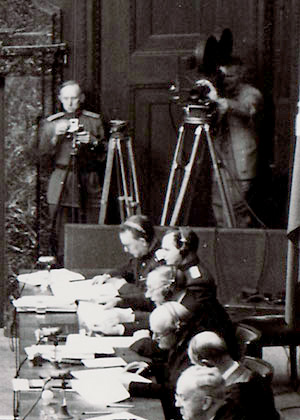

Portions of the Nuremberg trial were filmed with movie cameras operated by Army Signal Corps cameramen.

Two photographers and a 35mm movie camera in position at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Sound Recording in progress.

Sound engineers at the Nuremberg trial. (National Archives and Records Administration)

US Army Signal Corps sound engineers recorded Nuremberg trial proceedings in the four official languages: English, Russian, French and German. (National Archives and Records Administration)

The Making of Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today (1948)

The first Nuremberg trial (formally known as the International Military Tribunal) was convened November 20, 1945, in Nuremberg, Germany, to try the top Nazi leaders. The verdict was rendered October 1, 1946. The lead U.S. prosecutor, and the driving force behind the organization of the trial, was U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson. During preparation for the trial, Jackson made the bold and historic decision to use film and photo evidence to convict the Nazis. But these films had to be found.

Director John Ford, Commander of the OSS Field Photographic Branch

The Search for Nazi Footage

A special OSS film team was formed for this purpose, under the command of Hollywood director John Ford. Brothers Budd and Stuart Schulberg, sons of the former Paramount studio chief B.P. Schulberg, were assigned to this special OSS search team that was dispatched to Europe.

Sabotage and Success

The search for incriminating film was conducted under enormous time pressure, and they encountered sabotage along the way. They found two caches of film still burning, as though their guardians had been tipped off, and began to suspect leaks from their German informants, two SS film editors.

Just in time for the start of the trial, they found significant evidence, which, in close collaboration with Jackson’s staff of lawyers, they edited into a 4-hour film for the courtroom called The Nazi Plan. Jackson also presented their compilation of U.S. and British images from the liberated concentration camps, entitled Nazi Concentration Camps.

Documenting the Trial

Justice Jackson had wanted a film made of the Trial from the beginning. Its purpose was to be a dual one: 1) to show the German public that the Nazi leadership had been given a fair trial and had, essentially, “convicted themselves,” and 2) to create a film for posterity that would offer an enduring lesson for all mankind.

It was planned that Ford’s OSS unit would take charge of the filming, but they were so busy assembling footage to show at the Trial, that they had to decline responsibility. Thus, at the last minute, responsibility was shifted to another branch.

Army Signal Corps cameramen and still photographers filmed the Trial, but shot only 25 hours over the course of 10½ months.

Office of Strategic Services (OSS)

OSS: Training the Glorious Amateurs, (Central Intelligence Agency Archive)

Stuart Schulberg (foreground) & Bob Webb in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice editing room. (Ashkins Family Archive)

Field Photographic Branch

War Crimes Unit

NAVY LT. BUDD SCHULBERG, OSS officer in charge of compilation & editing The Nazi Plan, also writer of English inter-titles.

Budd Schulberg

OSS officer in charge of compilation & editing The Nazi Plan, also writer of English inter-titles.

Budd Schulberg’s first novel, What Makes Sammy Run?, was published in 1941 when he was 27 years old. A daring expose of Hollywood, it became an instant classic. ‘He’s a Sammy Glick’ has entered the lexicon as a descriptor for a man of ruthless ambition.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Budd Schulberg put down his pen and enlisted in the Navy. He was assigned to the Field Photographic Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Washington. There, under the command of Navy Commodore John Ford, he made secret training films.

In 1945, Ford charged Budd and his fellow officer Ray Kellogg with responsibility for locating incriminating film evidence that could be used at the Nuremberg trial. Budd’s young brother Stuart, also attached to Budd and Ray’s team, was sent ahead to begin scouting for material.

With Kellogg handling logistics, Budd wound up supervising the editing of The Nazi Plan, for which he wrote the explanatory inter-titles, and is sometimes credited as ‘director.’ The film is a compilation of footage that had been shot and directed by German filmmakers, including Leni Riefenstahl. During the editing process, Budd apprehended Riefenstahl as a material witness, and used her to identify Nazi officers in the thousands of feet of German footage, including her own.

Budd also supervised the editing of Nazi Concentration Camps, which shocked the courtroom when it was presented one week into the trial.

At the end of 1945, Budd returned to the U.S.,was discharged, and went to work on his second novel, The Harder They Fall. It was published to great acclaim. The movie adaptation starred Humphrey Bogart, and it turned out to be Bogart’s last movie.

Budd then created the Oscar-winning screenplay On The Waterfront. It won 8 Academy Awards in all, and made a huge star of Marlon Brando.

He followed that movie with A Face in the Crowd, which made stars of Andy Griffith and Patricia Neal.

His play The Disenchanted, inspired by his collaboration with F. Scott Fitzgerald on an ill-fated Hollywood movie, also became a literary classic.

His nonfiction works include Loser and Champion: Mohammad Ali, The Four Seasons of Success; Ringside: A Treasury of Boxing Reportage; Sparring with Hemingway; and his autobiography Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince.

Budd Schulberg died in 2009, aged 95. He was the lone survivor of the OSS Field Photographic Branch that located the Nazi films. At the time of his death, he was collaborating with his niece, Sandra Schulberg, on a book about the Schulberg brothers’ work for the Nuremberg trial, entitled The Celluloid Noose. He was also working on a screenplay with Spike Lee about the Max Schmeling-Joe Louis fight, and trying to complete the second volume of his memoirs.

ROBERT PARRISH, Film Editor

Bob Parrish

Editor

NEW YORK TIMES

Robert Parrish, 79, Film Editor-Director, Dies

By LAWRENCE VAN GELDER

Published: Wednesday, December 6, 1995

Robert Parrish, an Academy Award-winning film editor whose career in motion pictures took him from childhood acting in Chaplin’s “City Lights” to the director’s chair, died on Monday at Southampton Hospital on Long Island. He was 79 and lived in Sag Harbor.

Besides being an actor, editor and director, Mr. Parrish was a raconteur and writer whose recollections of his long career in Hollywood and abroad and wide range of friends among the most prominent names in film nourished two volumes of well-received memoirs.

Film is magic,” he said once as he discussed his career as an editor. “It will do anything you want it to do. I always believed in the director because Hollywood was a director’s town. I always tried to work as closely to what he wanted as I could.

“I knew that sweat was a lot of it. I had a cot put in my cutting room. I would recut something maybe five times in a night and run it again and again and again. I just knew it was sweat. I had no special touch or anything like that.”

As an editor, Mr. Parrish won an Oscar for “Body and Soul,” the 1947 Robert Rossen film that starred John Garfield as a money-grubbing, two-timing boxer on the make. Mr. Parrish and Rossen teamed again on “All the King’s Men,” an account of the rise and fall of a Louisiana politician that won the Academy Award for best picture in 1949.

Mr. Parrish was fond of noting that he won his Oscar — which he shared with Francis Lyon — in his first venture as a full-fledged feature-film editor. “I thought I’d get one every year,” he said.

As a director, Mr. Parrish earned plaudits for films like “Cry Danger,” a 1951 tale of revenge that starred Dick Powell; “The Purple Plain,” an Eric Ambler thriller that starred Gregory Peck in 1954, and “The Wonderful Country,” a 1959 western with Robert Mitchum.

As an actor, Mr. Parrish appeared in such films as the classic “City Lights” (1931); Lewis Milestone’s “All Quiet on the Western Front,” the winner of Academy Awards for best film and best director of 1930, and “The Informer,” which won John Ford an Oscar as best director in 1935.

After “The Informer,” Mr. Parrish became infatuated with the idea of becoming an editor. With Ford’s encouragement, he served his apprenticeship on such Ford classics as “Stagecoach,” “Young Mr. Lincoln” and “Drums Along the Mohawk” in 1939; “The Grapes of Wrath and “The Long Voyage Home” in 1940, and “Tobacco Road” in 1941.

He and Ford worked together again as members of the Navy’s Field Photographic Branch during World War II. Mr. Parrish was the editor of two Navy documentaries directed by Ford, “Battle of Midway” and “December 7th,” which won Academy Awards in 1942 and 1943 respectively.

When he returned from the war, Mr. Parrish won a promise from Harry Cohn, who led Columbia Pictures, that he would be given a film to direct if “All the King’s Men” proved successful. When it became a hit, Cohn reneged. But Dick Powell, at the time one of Hollywood’s few producer-directors, gave Mr. Parrish his chance with “Cry Danger.”

Mr. Parrish, one of four children, was born in Columbus, Ga., on Jan. 4, 1916. When he was 8, his family moved west and settled in Hollywood, “about 400 yards from Paramount Studios,” Mr. Parrish said.

“It was a small town,” he recalled, “and all the business was the movies. It was a factory, and the factory made movies. A lot of kids worked in the movies, because that’s where you could make some extra money.”

Mr. Parrish described his mother, the former Laura Virginia Reese, “as a card-carrying movie mother — she had four kids that worked in the movies.” She sent them out with some advice: “Say yes, no matter what,” Mr. Parrish remembered being told. “If they ask if you own a horse, say yes. If they ask if you are a horse, say yes. And you’ll learn how to do it that night.”

When he grew older and his parents’ marriage broke up, Mr. Parrish earned money dismantling sets after school and always found jobs as an extra.

Discussing his memoirs, “Growing Up in Hollywood” (1976) and “Hollywood Doesn’t Live Here Anymore” (1988), published by Little, Brown, Mr. Parrish remembered how Chaplin directed him and another youngster when they played newsboys tormenting the Little Tramp in “City Lights.”

“Charlie promptly stopped being the tramp and became two newsboys shooting peashooters,” Mr. Parrish related. “He would blow a pea and then run over and pretend to be hit by it, then back to blow another pea. He became a kind of dervish, playing all the parts, using all the props, seeing and cane-twirling as the tramp.

“We all watched as Charlie did his show,” he added. “Finally, he had it all worked out and reluctantly gave us back our parts. I felt he would much rather have played all of them himself.”

In addition to his wife, the former Kathleen Thompson, he is survived by a son, Peter, of Rockport, Tex., and a daughter, Kathleen Bottijliso of West Babylon, L.I.

JOSEPH ZIGMAN, Film Editor

Joseph Zigman

Film Editor

Joseph Zigman, who served as a film editor before the start of World War II, enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was assigned to the film unit of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services). The Field Photographic Branch, as it was officially called, was under the command of Hollywood director John Ford and was based in Washington DC, where the outfit made secret training films for OSS operatives. There he met two other sons of Hollywood – Budd and Stuart Schulberg – and the three formed a life-long friendship.

In September of 1945, as Budd and Stuart were still combing the Nazi territories for film evidence that could be used at the Nuremberg trial, Joe Zigman was sent to Nuremberg to compile and edit the footage that had already been found. He and his fellow editors Bob Parrish, Bob Webb and Patty O’Heir, cut together two historic films for the U.S. prosecution team to present to the Tribunal – The Nazi Plan (consisting entirely of German footage) and Nazi Concentration Camps (consisting primarily of footage shot by the Allied liberators). The photos and films presented in the courtroom played a vital role in convicting the Nazis on trial.

In the spring of 1947, Stuart Schulberg and Joseph Zigman teamed up again, this time to make the official film about the trial itself, Nuremberg: Its Lesson For Today. After Nuremberg was completed in 1948, Zigman stayed on in Berlin to edit de-Nazification and re-education films aimed at German audiences under the aegis of U.S. Military Government’s Documentary Film Unit, which was headed by Stuart Schulberg. When Schulberg was recruited to Paris to run the Marshall Plan Motion Picture Section, Zigman took over his production supervision duties at OMGUS in Berlin. In 1950, Zigman left Military Government and moved to Munich to serve as production manager, film editor and director for producer Eric Pommer on the early Flash Gordon TV serial, some episodes of which were filmed in Germany.

In 1954, Joe Zigman brought his family back to the United States in order to work on The American Week with journalist Eric Sevareid, ultimately becoming a widely respected “triple threat” as a producer, director and editor of network news and public affairs. His numerous CBS documentaries and special reports included Roger Mudd’s Ted Kennedy interview and countless news stories for famed anchorman Chet Huntley of NBC News.

For a brief period in the late 1950’s, he was also reunited with his old OSS mates Budd and Stuart Schulberg, who hired him to edit their Warner Brothers movie Wind Across the Everglades. This was one of the first films to tackle environmental issues, the killing of endangered species — the beautiful plume birds that were slaughtered to adorn women’s hats. The Audubon Society was instrumental in advocating for laws to protect these birds.

Joe Zigman worked on another film with an environmental theme, a documentary about the life of writer & naturalist Joseph Wood Krutch, whose work on ecological issues in the southwest include The Voice of the Desert. Zigman also went to Sierra Leone and Tanganyika (now Tanzania) to work on educational issues affecting the population there.

This precipitated his move to Hollywood in 1959, but a call from Chet Huntley in 1962 encouraged him to return to New York. After working on several documentary specials with Huntley, the CBS Evening News recruited him and he spent the remainder of his working career with Walter Cronkite as part of Cronkite’s famed CBS News team.

In 1981, Joseph Zigman retired to Oxnard, California, where he spent the last 15 years of his life. He died on December 1996 at the age of 80. As of 2011, he is survived by his wife Regina (Jeanie), daughter Judy Zigman Pantano of Brooklyn, son Louis Zigman of Los Angeles, four grandchildren and eight great grandchildren.

VARIETY

Dec. 17, 1996

Joseph Zigman

By VARIETY STAFF

Joseph Zigman, 80, longtime staff director and producer for CBS in New York, who, early on in his career helped assemble the secret Nazi film footage that was later used at the Nuremberg War Crime Trials, died Dec. 1 in Oxnard following a lengthy battle with prostrate cancer.

Zigman, who served as a film editor before the start of World War II, enlisted in the U.S. Navy and later joined the OSS Film Unit, which was led by Budd Schulberg.

In 1945 Zigman and others found Nazi archival footage that was used by the Four Powers prosecution during the Nuremberg Trials.

Zigman then settled in Hollywood and served as an editor on several features before moving to New York, where he became a producer and director on numerous CBS documentaries and special reports including Roger Mudd’s Ted Kennedy interview.

Zigman worked for many years with Eric Sevareid and Chet Huntley and on the “CBS Evening News” with Walter Cronkite.

Zigman is survived by his wife, Jeanne, a son and daughter, four grandchildren and one great-granddaughter.

ROBERT A. WEBB, Film Editor

Robert A. Webb, OSS film editor in his Navy uniform, c. 1944

(Photo courtesy of Gina Webb)

Film Editor

Robert Arlington Webb was born in Springfield, Illinois, on May 27,1911. His family moved to California in the 1920s, where his father and uncles worked in the Hollywood film industry. Brothers Harry Jr. and Jerry, and their brother-in-law, Harmon Jones, were all involved in filmmaking. For years, the Webb family lived at 524 North Bundy Dr. and in various houses nearby. Aside from the work Bob Webb did with the OSS in Germany, he spent a year or more in Burma, circa 1953, teaching a Burmese film crew the essentials of film editing. After returning to the U.S., he worked in New York City for the rest of his life, cutting commercials for various advertising agencies. He died in August 1971.

His nephew is Los Angeles film editor and screenwriter Robert C. Jones (son of Harmon Jones). Author of the Oscar-winning screenplay for Coming Home, Jones has also been honored for his film editing work with Oscar nominations for It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and Bound for Glory.

Photos below courtesy of Lieselotte Balte Ashkins

Ray Kellogg & Bob Webb (foreground) in the Nuremberg editing room, 1945

Bob Webb & Stuart Schulberg (at desk) in the Nuremberg editing room, 1945

Bob Webb in the Nuremberg editing room, 1945

STUART SCHULBERG, Writer

Stuart Schulberg

Writer/Director/Producer

Stuart Schulberg dropped out of the University of Chicago, where he had been majoring in journalism, to enlist in the Marine Corps after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to make secret training films for the OSS.

The OSS Field Photographic Branch, based in Washington, DC, was headed by Hollywood director John Ford. In the summer of 1945, Ford dispatched Stuart to Europe to hunt for Nazi films that could be used at the Nuremberg trial. His older brother Budd, of higher rank, followed and led what became a small team of editors and writers. During a frenzied 4-month period, the Schulberg brothers and their colleagues scoured the German-occupied territories for footage. The films and photos they presented in the courtroom played a role in convicting the Nazis on trial.

Subsequently, Stuart Schulberg wrote and directed NUREMBERG: Its Lesson for Today, the official documentary about the trial. After Nuremberg was completed in 1948, Stuart Schulberg produced denazification and re-education films aimed at German audiences in his role as chief of U.S. Military Government’s Documentary Film Unit in Berlin.

At the end of 1949, he was recruited to head the Marshall Plan Motion Picture Section in Paris, and served as its chief from 1950 to 1952. From 1952 through 1956, Stuart and his French partner, Gilbert de Goldschmidt, produced three commercial movies that addressed democratization and cultural tolerance issues within Germany, and between Germany and France. Starring well-known actors such as Joseph Cotten, these movies – No Way Back (Weg Ohne Umkehr), Double Destiny (Das Zweites Leben), and Embassy Baby (Von Himmel Gefallen) – were financed in part with covert U.S. government monies.

At the end of 1956, Stuart moved his family to the United States, in order to collaborate with his brother Budd on a movie for Warner Brothers, Wind Across the Everglades, starring Christpher Plummer, Burl Ives, Gypsy Rose Lee, and, in his first movie role, Peter Falk. One of the first films to tackle environmental issues, it dealt with the illegal killing of endangered species – the plume birds that used to adorn women’s hats at the turn of the century.

Thereafter, Stuart returned to his true passion, documentary films. In 1961, he was named co-producer of David Brinkley’s Journal, the first television news magazine, for which he won several all of the major awards in broadcast journalism, including the Emmy Award. As a result of its critical and popular success, he was named NBC’s Senior Documentary Producer, producing many of the important and award-winning network news specials of the 1960’s, with NBC’s top journalists David Brinkley, John Chancellor, Ed Newman, Robin McNeil, Sandy Vinocur, and others. In 1969, he was made producer of NBC’s fabled Today program,a position he used to expand the program’s domestic and international news coverage.

Stuart collaborated several more times with his brother Budd – on the television dramatization of Budd’s novel What Makes Sammy Run?; on the Broadway musical of Sammy; and on From The Ashes: The Angry Voices of Watts, a television special featuring the works of African-American writers who had emerged from the Watts Writers Workshop Budd founded in Los Angeles after the Watts uprising.

Stuart Schulberg died in 1979, aged 56, while producing his last major NBC special.

German Editors

CONRAD VON MOLO, UFA film editor

The son of Austrian author and writer Walter von Molo, Conrad Karl Ludwig von Molo was born in Vienna on December 21, 1906. The family moved to Berlin in 1914 and became German citizens.

Conrad von Molo worked as journalist, cutter, assistant director, and film synchroniser. He spent time abroad, eg, two years at Oxford University and Hounslow Studios in London.

During the war he worked as a film cutter at the UFA Studio in Berlin. In the late summer of 1945, he was attached to the OSS Field Photo Branch/War Crimes, to assist Ray Kellogg and Budd Schulberg on the editing of The Nazi Plan

LIESELOTTE “LILO” BALTE ASHKINS, Assistant Film Editor

Lieselotte “Lilo” Balte Ashkins

Assistant Film Editor

Born in Berlin in 1918, Lieselotte Balte was working as a film cutter at the famous UFA film studio in Potsdam in 1945, when Lt. Ray Kellogg chose her to assist the OSS Field Photo/War Crimes Unit with the assembly of Nazi film evidence to be used at the Nuremberg trial. As Lilo Balte recounted to Sandra Schulberg in June 2011, she was charged with making selects for the 4-hour evidentiary film that would be titled The Nazi Plan. These selects were pulled from the German newsreel series, Die Wochenschau, and from other German footage stored at UFA. Having worked as a newsreel film cutter, she was already familiar with much of the material. Once she had completed this process, Ray Kellogg brought Balte to Nuremberg to help them complete The Nazi Plan under the supervision of himself and Budd Schulberg. There she worked in the OSS editing room in the Palace of Justice with the American OSS film editors Robert Webb, Robert Parrish, and Joe Zigman, and alongside writer and still photography expert Stuart Schulberg. (The latter two men were later charged with making Nuremberg.)

Once The Nazi Plan was shown in the Nuremberg courtroom in December 1945, the OSS unit returned to the U.S. Balte remained in Germany, seeking whatever work she could. She re-opened her interior design studio that shut down during the war, worked as a production assistant at the new RIAS radio network, and as a German teacher and ski instructor for the U.S. Army at the Berchtesgaden American School and Recreation Area. It was in Berchtesgaden in 1951 that she met her future husband, Lawrence Ashkins, an Army paratrooper who was part of the U.S. occupation force. She eventually joined him in the south of France in 1953, where he moved after completing his doctorate in economics at the University of Paris. It was there that he began work on a novel inspired by his experience as an American Jewish soldier in Nazi Germany.

Getting Balte to America proved to be a challenge, and Ashkins had to leave her in Europe while he cut through more red tape in New York. Finally, in July 1954, with her sponsorship secured and paperwork in hand, Lilo Balte boarded the ocean liner Conte Biancamano in Cannes and sailed to meet her fiancé. Lilo Balte and Lawrence Ashkins were married in New York City on August 9, 1954, and she became an American. Their daughter Lisa was born while they lived in Washington D.C. They also resided in Ohio and Oregon before making San Diego their permanent residence in 1967. After more than 40 years of marriage, Lilo’s husband, Lawrence Ashkins, died June 17, 1995, in San Diego, California.

PHOTOS

Balte’s photographs, seen here, show members of the OSS film unit at work in the film editing room in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice.

Photos courtesy of Lieselotte Balte Ashkins

Ray Kellogg & Bob Webb (foreground) in the Nuremberg editing room, 1945

Bob Webb & Stuart Schulberg (at desk) in the Nuremberg editing room, 1945

Bob Webb in the Nuremberg editing room, 1945

German Informants

Germans reading about the Nuremberg verdicts in the Nuremberg newspapers, October 2, 1946. (Courtesy Nationaal Archief of The Netherlands)

When the film was first released in November 1948 in Stuttgart, rubble still lay in front of the Kamera cinema. (Schulberg Family Archive)

One of the original posters from the 1948 German release of NUREMBERG: Its Lesson For Today. (Schulberg Family Archive)

Crowd gathered beneath the banner for Nuremberg’s 1949 Berlin release. (Zigman Family Archive)

Poster for the Berlin run of Nuremberg, delayed until May 31, 1949, because of the Berlin blockade, with tagline that reads, “Symbol of the people’s judgment against international lawlessness,” implying that the German people agreed with the Nuremberg verdicts. (Schulberg Family Archive)

Creating the Film About the Trial

In the winter of 1946, Stuart Schulberg and his editor, Joe Zigman, were commissioned by Pare Lorentz (head of the Film/Theatre/Music in the Civil Affairs Division of the U.S. War Department of War) to create a documentary about the trial.

Schulberg and Zigman found themselves terribly constrained by the available footage. Crucial coverage simply did not exist. On the other hand, a complete sound recording of the trial was made. In an article that Stuart Schulberg wrote in 1949, he described the frustrating process:

“The greatest technical difficulty involved the use of original recorded testimony from the trial itself. It was important, if the film’s authenticity was to be convincing, that Goering and his colleagues speak their lame lines of defense in their own, well-known voices…It became necessary to secure the wax recordings of the proceedings stored in Nuremberg, to re-record the pertinent words on film and then to synchronize that sound recording with the lip movements of the respective defendants…. Many weeks after the original request, the records arrived from Nuremberg. The discs were re-recorded on film in half of one day, and about a month later the meticulous job of ‘dubbing’ the original voices of the defendants was completed.” (Stuart Schulberg, Nurnberg, Information Bulletin, No. 164, June 28, 1949, Office of Military Government for Germany, Berlin.)

A Political Minefield

Just as the impetus for the trial had come from the Americans, so the Americans sought from the beginning to control production of the film about the trial. But, in the fall of 1946, disagreements about the script and filmmaking process arose, not only within the four-power Documentary Film Working Party (DFWP), but also between the U.S. Military Government in Berlin and the War Department in Washington.

By the spring of 1947, Pare Lorentz, Chief of the Film, Theater, Music (FTM) Section of the War Department’s Civil Affairs Division (and creator of The Plow That Broke the Plains and The River) had finally won control of the film, and was sending his writer-director designate, Stuart Schulberg, to Berlin.

The first German audiences emerge from the Kamera cinema in Stuttgart, November, 1948. Their reactions, as recorded by OMGUS pollsters, ranged from disbelief, to anger, to shame.

The German Premiere

Schulberg and editor Joseph Zigman completed the 78-minute film in Berlin in early 1948, and chose as its final title, Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today. It was shown to West German audiences for the first time in November 1948, in the city of Stuttgart. Because of the Soviet Blockade of Berlin, the premiere in that city was delayed until May 1949.

Stuart Schulberg at the Stuttgart premiere of Nuremberg in 1948. (Schulberg Family Archive)

THE FILMS WITHIN THE FILM

Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today derives power from its stark, black & white cinematography, the use it made of the Nazis’ own propaganda films, the testimony of such infamous figures as Hermann Goering, and from the devastating, heart-rending images of human cruelty.

The Schulbergs’ OSS Field Photographic Branch/War Crimes Team prepared a 4-hour compilation of fully authenticated German material, which was screened in the courtroom on December 13, 1945, under the title, The Nazi Plan. It traced the Nazi rise to power, beginning in 1920s and continuing through the war. This evidentiary film was, towards the end, constructed hand-in-hand with the prosecutors, and became an important element of the prosecution’s case.

They also compiled a 1-hour film called Nazi Concentration Camps. This was a specially edited version of Army Signal Corps Atrocity Film, filmed at camps that had been liberated by the Americans and British in May 1945, including Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, Mauthausen, Nordhausen, Ohrdruf, and at Hadamar, where doctors performed hideous experiments on people.

Other footage screened at the trial included a 60-second 8mm film of Jewish men and women being dragged (some of them naked) from their homes; and two films presented by Soviet prosecutor Roman Rudenko, German Fascist Atrocities in the USSR, and The Destruction of Lidice.

During the editing period in Berlin, Stuart Schulberg located a historic piece of film in the Berlin apartment of a Nazi SS officer named Nebe, showing the experimental gassing of human beings in a small outbuilding on the outskirts of Mogilev, Poland. Schulberg chose to include that footage in the film, even though it had not been shown at the trial.

(The papers of Stuart Schulberg revealed that he added the sound effect of the car’s engine running. That sequence, now with the sound removed, forms part of a special “Deadly Medicine” exhibit at the Holocaust Museum.)

One of the documents in Stuart Schulberg’s files on the Nazi concentration camps. The German caption reads: This inmate was still alive when he was found on his bed of straw in the main barrack, but died shortly thereafter.

Director Leni Riefenstahl filming Olympia. (Courtesy Deutsches Bundesarchiv)

Photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, father-in-law of Nuremberg defendant Baldur von Schirach. (National Archives and Records Administration)

The Nazi Plan

The lead U.S. prosecutor, and the driving force behind the organization of the Trial, was U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson. During preparation for the trial, Jackson made the bold and historic decision to use film and photo evidence to convict the Nazis. But these films had to be found.

A special OSS film team — OSS Field Photographic Branch/War Crimes — was formed for this purpose. Brothers Budd and Stuart Schulberg, sons of the former Paramount studio chief B.P. Schulberg, were assigned to this special OSS search team that was dispatched to Europe. Budd was a Navy Lieutenant, and his younger brother Stuart, a Marine Corps Sergeant.

Stuart Schulberg and another office from the film unit, Daniel Fuchs (later a well-known author), were sent first, in June 1945. Budd Schulberg, along with OSS film editors Robert Parrish and Joseph Zigman, followed in September 1945.

The search for incriminating film was conducted under enormous time pressure, and they encountered sabotage along the way. They found two caches of film still burning, as though their guardians had been tipped off, and began to suspect leaks from their German informants, two SS film editors.

Just in time for the start of the trial, they found significant evidence, which, in close collaboration with Jackson’s staff of lawyers, they edited into a 4-hour film for the courtroom called The Nazi Plan.

In the course of this work, Budd Schulberg apprehended Leni Riefenstahl at her country home in Kitzbühl, Austria, as a material witness, and took her to the Nuremberg editing room, so she could help Budd identify Nazi figures in her films and in other German film material his unit had captured.

Stuart Schulberg took possession of the photo archive of Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s personal photographer, and became the film unit’s expert on still photo evidence. Most of the stills presented at the trial carry his affidavit of authenticity.

The Nazi Plan was presented as evidence on December 13, 1945, preceded by an affidavit of authenticity signed by Commander Ray Kellogg, Budd’s immediate superior. As The Nazi Plan consists entirely of footage shot by Reich officers, cinematographers and directors (e.g. Riefenstahl), Budd Schulberg wrote English-language inter-titles for the compilation film.

Nazi Concentration Camps

Justice Robert H. Jackson shocked the courtroom on November 29, 1945, when he decided to present Nazi Concentration Camps, a 1-hour compilation of U.S. and British motion picture material that was shot as the Allies were liberating some of the concentration camps.

In a letter published in 1947, Stuart Schulberg described how, at the last moment, on the morning of the presentation, he taped neon tubing under the armrest of the prisoners’ dock, so that it would be possible to see the defendants’ reactions to the film in the darkened courtroom.

When Stuart Schulberg and his editor, Joseph Zigman, made Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today, they intertwined the courtroom scenes with excerpts from The Nazi Plan and Nazi Concentration Camps.

A full account of the search for the Nazi photographs and film footage conducted by Budd Schulberg, Stuart Schulberg, and their OSS colleagues, appears in a forthcoming book called The Celluloid Noose.

General Eisenhower reviewing the carnage at Ohrdruf concentration camp on April 12, 1945, the first to be liberated by the American Army.

U.S. Suppression of Nuremberg

Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today was meant to be shown in the United States as a stirring example of American and Allied justice, and as a lesson for posterity, but the film’s U.S. release was apparently suppressed, despite the fact that, in April 1947, Assistant Secretary of War Howard C. Petersen had written:

“The very way in which the Trial was set up and conducted and the evidence which it produced constitute an historical document that should be of use, not only in motion picture theaters, but in schools and universities for many years to come.”

(Source: Carbon copy of letter from Assistant Secretary of War Howard C. Petersen to General Lucius D. Clay, American Military Governor of Germany, in the Schulberg Family Archive.)

Variety, June 11, 1947 (Schulberg Family Archive)

Superseded by the Soviets

By this time, the Soviets had decided to produce their own film, Sud Narodov (Judgment of the People), which they released not only in Germany, but also in New York. On May 21, 1947, the New York Post reported:

“The Stanley Theatre in Times Square will show the Nuremberg Trial film. But this is the Russian version. The complete, four-power movie is being made by Pare Lorentz and will be ready in two months…Schulberg & Zigman are in Berlin completing the movie based on the official transcript and stressing the real philosophy of the trials.”

But that same month, Lorentz (in the U.S.) cabled Schulberg (in Berlin) that he was resigning his post in frustration, although he hoped to remain involved with the film.

Two weeks later, on June 8, 1947, Variety began digging behind the scenes and reported: “Internal U.S. Army Snarl let Reds Beat Yanks on Nuremberg Film.”

Washington Post Exposé

In 1949, a dogged Washington Post reporter named John Norris tried to investigate why the War Department would neither release the film itself, nor sell it to Pare Lorentz so that he could complete and distribute the English-language version. No one would go on record.

Norris presumed that wide release of a film indicting Germany on war crimes might impede political and public acceptance of the plan to rebuild Germany’s economy, a vital plank in the Marshall Plan’s approach to European recovery.

To complicate matters, in the middle of 1948, the Soviets blockaded Berlin. The new threat was Soviet expansionism. While attempting to ferret out the reasons for the government’s censorship of the film, Norris speculated that some “have suggested that there are those in authority in the United States who feel that Americans are so simple that they can hate only one enemy at a time. Forget the Nazis, they advise, and concentrate on the Reds.”

Thus, the English-language version was never properly finished and never released to theaters in the United States.

CREDITS

ORIGINAL 1948 FILM

Written & Directed by

Edited by

Produced by

Stuart Schulberg & Pare Lorentz

Production Supervisor

Musical Score by

CREDITS (partial listing)

FILM RESTORATION

Restoration created by

Sandra Schulberg & Josh Waletzky

Restoration Executive Producer

Narrator

Senior Archival Researcher

Score Reconstruction

Consultants

Raye Farr, Les Waffen, Ronny Loewy, Karin Kuehn,

Christian Delage, Sergei Kapterev

Restoration Production Companies

Schulberg Productions & Metropolis Productions

Sound editor & recording engineer John Bowen, at Sync Sound, used two microphones to record Liev Schreiber’s narration, September 22, 2009.

Steve Blakely indicating the cut in the negative that Sandra Schulberg decided to make, thus eliminating the Zeit im Film bumper from the beginning of Nuremberg.

Stan Stzaba taking the new negative to his studio to make the cut, October 2009.

DuArt’s Steve Blakely checking the new 35mm Nuremberg negative (Photo Sandra Schulberg)

DuArt’s Joe Monge with first 35mm print of the Nuremberg restoration (Photo Sandra Schulberg)

The Three Restoration Challenges

The restoration involved two major challenges, one pictorial, and one aural. Along the way, a third challenge appeared – this one musical.

First: Creating a New Negative

It was decided at the outset that the first 1948 version of the film would be the standard, and that no picture element would be changed. But with the original negative lost, what master material could be used? Sandra Schulberg had been consulting with Les Waffen, the Motion Picture chief at NARA (U.S. National Archives & Records Administration), about this question for several years, and they planned to use a 35mm print kept in cold storage in Kansas. On close inspection, however, the image was too degraded and the contrast too high. Another NARA print and two duplicate negatives were also inferior candidates; and they varied in length, which meant frames or entire shots had been cut. With time growing short, the Berlin Bundesarchiv came to the rescue, and shipped its 35mm “lavender” print — a fine grain master positive — to the U.S. on loan.

There was jubilation when the inspection report showed each of the eight reels in excellent condition, with minimal shrinkage. The picture contained more detail, and the low contrast meant the lavender print offered the best chance to create a good quality negative. The German print was also the most complete print in existence, and its German language soundtrack was crisp. By the end of September 2009, a new 35mm film negative had been created under the supervision of Russ Suniewick at Colorlab, in Rockville, MD, a facility that specializes in archival restoration and preservation. The negative was then sent to DuArt Film & Video in New York, where new 35mm release prints were made under the supervision of DuArt Chairman Irwin Young, and his associate Steve Blakely.

The restoration team examined 6 different versions of Nuremberg to find the best print from which to make a new negative. Here two are compared, NYC, July 2009. (Photo by Sandra Schulberg, courtesy Schulberg Productions)

Second: Reconstructing the Sound Track

Meanwhile, a complex sound reconstruction was underway. Sandra Schulberg and Josh Waletzky’s goal was to create an international soundtrack that would permit modern audiences to hear the voices of the English-, French-, and Russian-speaking prosecutors, and the voices of the German witnesses, defendants and defense attorneys. They also wanted audiences to hear the original German spoken in The Nazi Plan, the evidentiary film presented at the trial that weaves in and out of Nuremberg. Stuart Schulberg had emphasized the importance of hearing live sound at the time:

“The greatest technical difficulty involved the use of original recorded testimony from the trial itself. It was important, if the film’s authenticity was to be convincing, that Goering and his colleagues speak their lame lines of defense in their own, well-known voices… It became necessary to secure the wax recordings of the proceedings stored in Nuremberg, to re-record the pertinent words on film and then to synchronize that sound recording with the lip movements of the respective defendants… Many weeks after the original request, the records arrived from Nuremberg. The discs were re-recorded on film in half of one day, and about a month later the meticulous job of ‘dubbing’ the original voices of the defendants was completed.”

(Stuart Schulberg, article titled Nürnberg, Information Bulletin, No. 164, June 28, 1949, Office of Military Government for Germany, Berlin.)

With Lisa Hartjens duplicating the trial recordings at NARA, Josh Waletzky began the painstaking work of trying to match them to picture. Here he encountered the same problems faced by the original filmmakers, Stuart Schulberg and Joe Zigman. Although it was Stuart Schulberg’s wish to use as much original sound from the trial as possible, he was relatively limited. He and Zigman got around the problem by using extensive narration and picture that was not synchronized to sound. In the subsequent English-language version of the film, all of the voices – German, French, Russian, and English – were almost entirely obscured by narration. The sound reconstruction required laborious patience – and many compromises. It became obvious that sync would remain an elusive goal, even where it was possible to substitute live sound for narration.

While Waletzky finessed the sync sound issues, Schulberg concentrated on the creation of subtitles to mesh with new narration. Thanks to Stuart Schulberg’s documents, she had access to the original German and English scripts. With the help of Jenny Levison and Lisa Hartjens, an English-German “dialogue list” was transcribed. Then began the fascinating job of comparing the dialogue list with the original scripts, with the 1948 English and German narration tracks, with the spoken words recorded at the trial, and with the court transcript. Many translation issues arose.

How accurately did the original narration translate what was being said at the trial? To what extent did the narration reflect the prosecution’s spin on the testimony and textual evidence? To what extent did the narration reflect a noticeable “re-education” point of view on the part of U.S. Military Government? How much liberty could be taken to clean up cumbersome syntax and improve on the translation without changing the character of the original film? Should one use the English term “Final Solution” for what Goering referred to as the “Endlösung der Judenfrage?” Another tricky example was translation of the word “Weltanschauung,” which the original film conveyed as “ideology.” Schulberg and Waletzky (who speak German and Yiddish respectively) pondered and debated the right word choices in the weeks leading up to the recording session, and again before the subtitles were burned into the first 35mm print.

September 22, 2009 was an exciting day. Liev Schreiber (star of Taking Woodstock, Defiance, The Manchurian Candidate, etc.) recorded the voice-over script at Sync Sound in New York. To preserve the aural ambience of the original track, a period RCA microphone was used in addition to a state-of-the-art Neumann. Schreiber’s vitality, and his ease with all the German pronunciations, infused the narration with a fluid energy.

Third: Recreating the Original Score

The search for the original music tracks had begun in July. Without them it would be impossible to excerpt those sections of the score that were married to the narration. Ronny Loewy, one of the Nuremberg film experts in Germany volunteered to search. Although hope of finding the music tracks quickly dimmed, Loewy reported surprising news. The composer was Hans-Otto Borgmann, who, in 1933, had composed the music for a Nazi propaganda film Hitlerjunge Quex. One of his songs from the film – Unsere Fahne flattert uns voran, with lyrics adapted from a text by Baldur von Schirach – became the official anthem of the Hitler Youth.

Borgmann’s apparent ties to the Nazi Party stunned Schulberg and Waletzky. How could he have been cleared to work on Nuremberg?

Bundesarchiv researcher Babette Heusterberg reported that Borgmann had been a member of Nationalsozialistische Betriebszellenorganisation (NSBO), the Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (KfdK), and the Reichsfilmkammer, but there was no evidence of his membership in the Nazi Party (NSDAP). According to records she found, Borgmann was interviewed by the Office of Military Government, Information Control Branch, in Berlin on October 20, 1946, and barred from all cultural activities. He waited some months before filing for an employment permit again, citing a possible job offer from Eric Pommer, chief of the OMGUS Motion Picture Branch. The files show that Borgmann’s case was reconsidered on September 5, 1947. By then, the U.S. Army had no objection to his employment in the U.S. Sector, and reclassified him. He had his Persilschein.

(Persil was the name of a popular laundry detergent in Germany. Persilschein entered the postwar vocabulary as a slang term to mean a denazification certificate or work permit issued by the occupying governments. In political terms, it signified a clean bill of health, but could also mean a whitewash.)

The music tracks were lost, but Schulberg found Borgmann’s handwritten, fully-orchestrated, musical cues for the Nuremberg film in her father’s files. With this as guide, composer John Califra synthesized the music obscured by the original narration. He worked closely with Waletzky, a composer himself, to precisely match the reconstructed music to the rest of Borgmann’s score. Another enormous problem had been solved.

Elwin Hendrikse, coordinator of the Nuremberg restoration project on behalf of the Nationaal Archief of the Netherlands. (Photo by Sandra Schulberg, June 2009)

Sound mixer Ken Hahn (at left), producer Sandra Schulberg, and sound designer Josh Waletzky celebrate successful completion of the Nuremberg sound mix, October 2009.

Restoration Credits

Team

Co-Creator/Producer

Co-Creator/Sound Design

Narrator

Executive Producer

Duplication of Trial Recordings

& Senior Archival Researcher

Score Reconstruction

Music Consultant

Marco Swados

Music Consultant

Sound Editor

Re-Recording Mixer

Casting Consultant

Production Assistant

Consultants

Director, Steven Spielberg Film & Video Archive, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

Chief, Motion Picture, Sound & Video Branch, U.S. National Archives & Records Administration

Project Manager, Cinematography of the Holocaust, Fritz Bauer Institut & Deutsches Filminstitut

Filmarchiv der Bundesarchivs, Berlin, Germany

Historian / Scholar

Christian Delage

Historian / Scholar

Labs

President, Colorlab Corp.

President, DuArt Film & Video

DuArt Colorist

DuArt Senior Editor

Negative Cutter

LVT Laser Subtitling – New York

Archival Partners

![]()

NATIONAAL ARCHIEF OF THE NETHERLANDS

In 2009, the Nationaal Archief of the Netherlands made a significant financial contribution to the Schulberg/Waletzky Restoration of Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today. In collaboration with the Erasmus Prize Foundation, it hosted the world premiere of the restored film in The Hague on November 13, 2009.

For more information, click here.

For more information about the World Premiere at The Hague & the Amnesty International “Movies that Matter” Film Tour click here.

NARA – THE U.S NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Schulberg Productions has worked closely with the Motion Picture Branch of NARA, especially Les Waffen, since embarking on the restoration and preservation of the films of the Marshall Plan in 2003, and subsequently on the restoration of Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today.

For more information, click here.

GERMANY’S BUNDESARCHIV – FILMARCHIV

The Bundesarchiv is the German government’s official archive, holding public and private records originating from the German Reich, the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany. The Bundesarchiv is a government agency under the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media within the Federal Chancellery. It constitutes the main executive body charged with safeguarding of the national film heritage. The Bundesarchiv’s motion picture department — the “Filmarchiv” — is staffed by about 100 people. It is associated with other German film archives and film institutions, and its mandate is to serve as the central German film archive responsible for collecting, cataloguing, preserving and providing access to the whole range of German or German co-produced films (except TV productions). For the restoration of Nuremberg, the Filmarchiv provided its best surviving 35m print to Schulberg Productions, on loan, which was arranged by restoration collaborator Karin Küehn.

For more information, click here.

The Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive

THE U.S. HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

Schulberg Productions is indebted to the staff of the Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive, especially its Director, Raye Farr, for their extraordinary level of research assistance and morale support on the Nuremberg film restoration. Sandra Schulberg began to work closely with Raye Farr and the Archive in 2005, and the Archive and its staff has played a vital role in achieving the project’s ambitious restoration objectives.

For more information:

Film and Video Archive

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW

Washington, DC 20024-2126

Tel.: (202) 488-6104

Fax: (202) 314-7820

E-mail: filmvideo@ushmm.org

Web Site: Click here

A living memorial to the Holocaust, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum inspires citizens and leaders worldwide to confront hatred, promote human dignity, and prevent genocide. A public-private partnership, federal support guarantees the Museum’s permanence, and its far-reaching educational programs and global impact are made possible by donors nationwide.

For more information, click here.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW

Washington, DC 20024-2126

Main telephone: (202) 488-0400

TTY: (202) 488-0406

Significance for Civilization at Large and for the Jewish Community

Survivors photographed at Buchenwald concentration camp, when it was liberated by the American Army, April 13, 1945.

For Jews, the trial held, and still holds, a special significance. It served as the first acknowledgement that Jews had been Hitler’s primary victims.

Yet Holocaust deniers still exist and make news 60 years later, finding fertile ground. Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today recreates the incontrovertible proof that clinched the prosecution’s case; yet virtually no one has ever seen the film. For although the film was widely shown in Germany during 1948 and 1949, as part of the postwar campaign to denazify and re-educate German society, the very government officials who had paid for the film to be made got cold feet about showing it to American audiences.

The Schulberg/Waletzky Restoration comes at an opportune time, for the “Nuremberg principles” are now being applied around the world in an effort to prosecute crimes against the peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.